Introduction

General

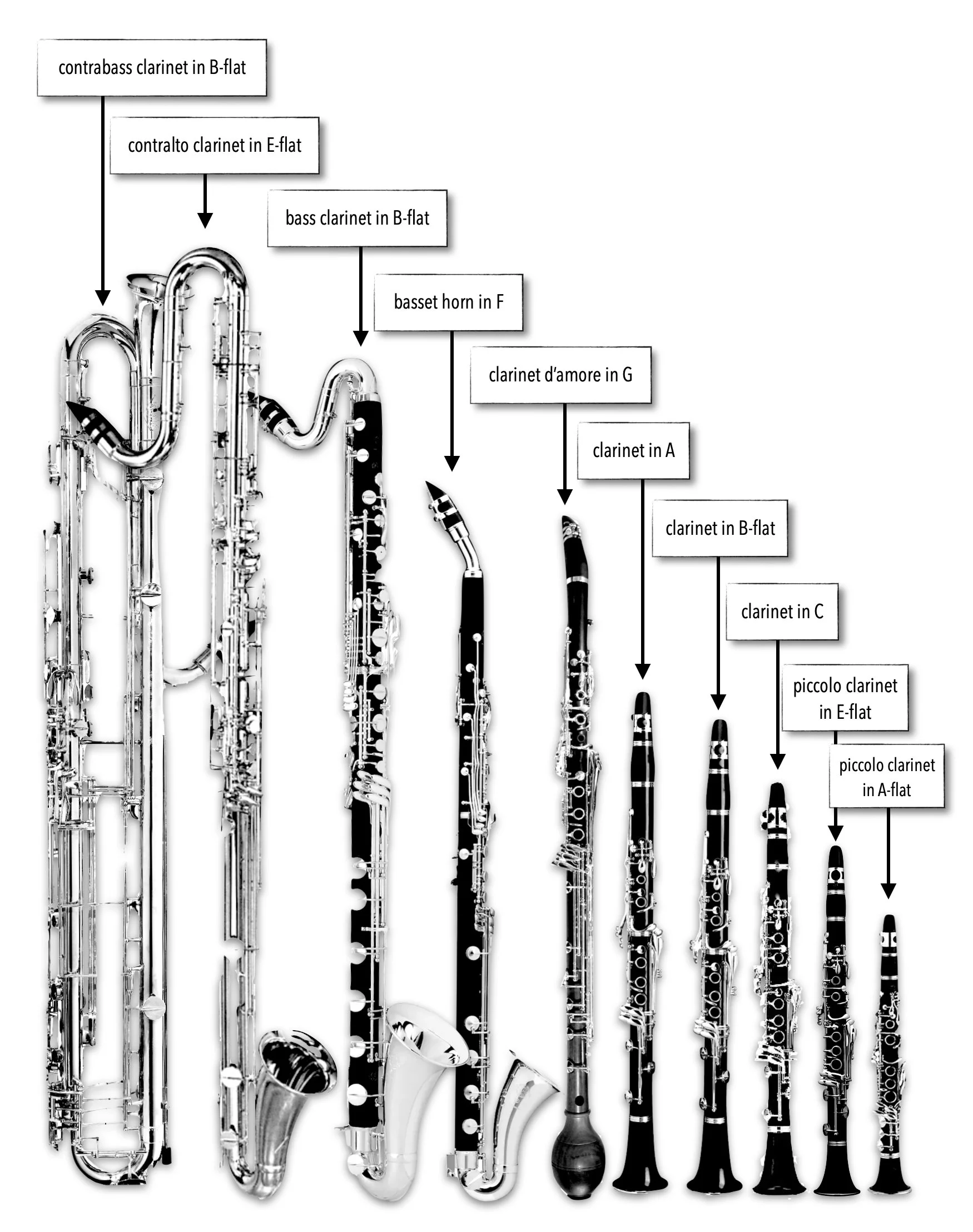

Illustration indicative of relative sizes of clarinets © Richard Elliot Haynes 2023

Clarinets come in many sizes and transpositions and were developed for different contexts such as salon, chamber, folk, military and orchestral music. The individual sonic characteristics of each clarinet can bestow your music with a unique sound, particularly when used in inventive instrumental combinations. If you are a composer and/or arranger and will be writing/scoring for clarinet, you might be wondering which clarinet or clarinets to choose, which clarinets to form a clarinet section or which clarinets to combine with other instruments. As you surely already know, there are many different kinds of clarinets to choose from — some with varying degrees of availability — so how does one choose which one/s to write for? This guide aims to help you decide which clarinet — or constellation of clarinets — is right for your new composition or arrangement.

It's important to note at this stage that a lot of the information contained in this article is generalised. An attempt has been made to remain as objective as possible — even though describing the sound of instruments is very much a subjective practice — so as to not favour one clarinet or the other. The descriptions are based on existing repertoire and my experience of the sound of the instrument. There are so many aspects to each and every instrument just as there are manifold considerations for every composition/arrangement. The information is intended to give you more insight into the nature of each clarinet.

In all of my explanations of instrumental range or in specifying pitch, I maintain usage of both the Helmholtz and Scientific Pitch Notation, with some very few exceptions.

Woodwinds

The woodwind family offers many auxiliary instruments in addition to the standard flute, oboe, clarinet and bassoon. If we include the saxophone and recorder families, there are even more. Clarinets however have some of the largest ranges, in part thanks to the fact that the instrument overblows at a 12th, instead of an octave. Take a look at this comparison (right) of the approximate ranges of the four main orchestral woodwind instruments and their auxiliaries (not all variations of these instruments have been considered). Defining ranges of instruments is however not an exact science: there are just too many models and variations out there. The lowest note of a woodwind instrument is generally a purely mechanical fact. The highest note is a combination of the player’s setup (type of mouthpiece, type/strength of reed, skill of the player and in some cases instrument mechanics). Always be wary when you are approaching the top of an instrument’s range and if you don’t posses first-hand experience, ask someone that does. It might save you a lot of time later, when you have to re-orchestrate chords or re-write a fancy solo passage. The highest pitches cited here (right) are of an advanced, professional level. Variations of lowest pitch can occur with the following instruments, so ask your local player: contrabassoon (low A?), contrabass clarinet (low C?), contralto clarinet (low C?), bass clarinet (low C?), bass flute (low B?), cor anglais (B-flat foot?), alto flute (low B?) and flute (low B?). Ask them, it’s a good excuse to pick up the telephone and talk to another human being.

French, German, what?

If you happen to be reading this because you are writing for me, I play Boehm-system clarinets, often called French system. Most of the clarinettists on the planet play this system. Oehler-system, or more commonly German system is played predominantly in Germany and Austria, and then relegated mostly to orchestras. The descriptions of the sound of each instrument found in each individual section of this guide can be applied to both Boehm and Oehler-system instruments. If you are writing using extended techniques — especially multiphonics — there are quite large differences between the two systems. For Boehm-clarinets, there are well-known books by Bartolozzi, Farmer, Rehfeldt, Richards and Sparnaay that all deal with extended techniques on various types of clarinets, so you can feel free to use these as a reference. If you need a text for Oehler-system, Krassnitzer’s Masters Thesis is worth a look. If you are looking for extended techniques for a more rare instrument, for which there is not yet a dedicated book, you can adopt techniques for eg. B-flat or bass clarinet and apply them to 'nearby' clarinets, bearing in mind that the results may vary. Here’s an overview:

piccolo clarinets in A-flat, G, E-flat & D — charts for any high clarinet

clarinets in C, B-flat & A — charts for any high clarinet

clarinet d’amore/basset horn in G — mostly high clarinet charts, some aspects of bass clarinet charts

basset horn in F/alto clarinet — mostly bass clarinet charts, some aspects of high clarinet charts

bass clarinet — charts for bass clarinet

contralto, contrabass clarinets — dedicated charts for these instruments

It's extremely important to check anything from these books/charts with the player for whom you are writing and on the specific instrument in mind!

Transposition

Almost all clarinets are transposing instruments, which means that the player reads from a part, or a score that is transposed according to the instrument being played. The term "in C" means that an instrument is a non-transposing instrument, or transposes at the octave (eg. piccolo, contrabassoon). The preposition "in" does not imply that an instrument is pitched in any type of key (eg. C major, B-flat major etc.) it simply denotes the nominal pitch of the instrument, which means that when the instrument plays a C4 (c’) (or in any other octave…), the resulting pitch is the same as the nominal pitch of the instrument (see illustration above). When the B-flat clarinet plays a C4 (c’), it sounds as a B♭3 (b♭). When the clarinet in A plays a C4 (c’), it sounds as a A3 (a). The nominal pitch is the most objective descriptor of the instrument as it gives us little to no information about the sound of the instrument. It’s just a label, however it’s an important label because it tells us how it transposes and thus how one scores for it.

A simple example of transposition occurs at the beginning of every rehearsal and concert with the tuning note A4 (a’): because the B-flat clarinet is pitched one whole tone lower than C, it needs to play one whole tone higher than A4 (a’) in order to tune, which is a B4 (b’). The clarinet in A however, being pitched a minor third lower than C, needs to play the A4 (a’) a minor third higher in order to be in unison and so plays a C5 (c’’). The basset horn is pitched in F, a perfect fifth lower than C, so it must play the A4 (a’) a perfect fifth higher, an E5 (e’’).

If you know the instrument well and have no trouble reading transposing scores, it can be worthwhile to compose/arrange directly to a transposing score. Using a C score and transposing later (otherwise known as using the "transpose" button) can lead to some problems if a) you don’t know the sounding instruments’ ranges from memory and write higher or lower than they are capable of playing (the stock standard ranges in the notation software Sibelius are often misleading) or b) you don’t fully understand the sounding registers of the instrument and therefore write passages in non-idiosyncratic, inconvenient or counterproductive ways. As all clarinets have a relatively similar transposed (written) range, you can train yourself to know what the resulting pitches are whilst working with a transposed score, and you will know at all times which register of the instrument is being used. (More on register later…)

One final thing to note about transposition and computer notation software is this: if you are writing atonal/experimental music and don’t specify that your work is atonal in the program, then it will add a key signature to transposed parts, which isn’t very helpful for atonal/experimental music. This can be very irritating for performers and can slow down the process of learning your music. Please pay attention to this whenever you are writing for transposing instruments.

Register

All clarinets exhibit a division into three main registers: chalumeau, clarion and altissimo. The upper minor third of the chalumeau is often called the throat. These registers are determined by fundamental physical characteristics of the instrument that dictate that the clarinet overblows at a perfect 12th and then a major 6th. To be thorough, there are further register breaks within the altissimo but as these become more frequent and arguably less consequential for the sound, they are grouped here into one register.

The illustration of the transposed/written clarinet registers shows the three registers and their notional lowest and highest pitches. Chalumeau: on instruments with a basset extension (some clarinets d’amore, all basset horns, most bass clarinets, most contrabass clarinets) the lowest chalumeau pitch is C3 (c), a major third lower than shown here. Most alto and contralto clarinets have a lowest note of E♭3 (e♭), a semitone lower than shown here, and some have a range to low C (c). Please keep this in mind. It is possible to blur the boundaries of the register break between chalumeau and clarion with unconventional fingerings. In doing this, the chalumeau can extend up to C5 (c’’), however the intonation of these pitches can be questionable. Clarion: using unconventional fingerings, one can extend the clarion up to about F6 or F♯6 (f/f♯’’’) but the intonation and stability of these pitches require experience to master. Instruments with a basset extension can extend the clarion register down almost to a G4 (g’) but the intonation of these pitches differs greatly from instrument to instrument and so the regular fingerings are recommended. Altissimo: although one can overblow written B4 (b’) and subsequent pitches to effect an earlier transition to the altissimo, the normal point at which the altissimo is played is from C#6 (c#’’’) whose fingering is based on a clarion E5 (e”). Even though these main register breaks are the same on each clarinet, the ramifications of each break can vary: larger clarinets will have more noticeable register breaks due to the — very generally speaking — change in the amount and size of open and closed tone-holes as well as a more complicated register mechanism. Smaller clarinets are more fluid in this regard.

The highest possible (transposed) pitch of the altissimo register is quite variable (denoted by the “+” next to the highest notional pitches). A good rule of thumb is this: for the highest clarinet (piccolo clarinet in A-flat) don’t write above G6 (g’’’) without asking the player you’re writing for. For the lowest clarinet (contrabass clarinet) don’t write above G7 (g’’’’) without asking the player you’re writing for. All the clarinets in between have reliable highest notes somewhere within this octave from G6 (g’’’) to G7 (g’’’’). This is shown in more detail later on.

Nearby and distant range / tone colour pairings

Within each clarinets’ description you will notice two short indicative lists of both nearby and distant instrumental pairings. First of all, these are purely suggestions and based on my experiences in ensembles and orchestras as well as general knowledge of range and tone colour. The second thing to note here is that the perception of tone colour can be influenced by the audible presence of other instruments, especially when the musical texture is relatively transparent. The third thing to remember is that the effect on the combined sound depends on if the instrument (or instruments) is playing in a strong, weak, comfortable or extreme area of their range. Here’s some food for thought:

high-range clarinets: These instruments are often used as solo instruments, regardless of instrumentation (chamber, large ensemble, orchestra etc.). What might be gained by having a high clarinet play the lowest part of the harmony? Would this work in a louder or softer dynamic? Which instruments would be suited to playing the upper voices, in order to balance with a high clarinet in its lowest register?

mid-range clarinets: Often called — for good reason — harmony clarinets, these instruments are known to fill out the harmony as needed, but of course, they can do much more than this. If one were to take these instruments out of their usual orchestrational context, where would they go? Delicately woven meanderings within a brass chorale? A high unison passage with the 1st violins? A prominent melody accompanied by a team of oboes?

low-range clarinets: The bass department of the clarinet family likes it low, but they like to — pardon the pun — get high, too. How could the altissimo registers of the bass, contralto or contrabass clarinets be infused with the seductive sound of flutes in their lowest register? How might a low clarinet extend the resonance of tuned percussion, harp or piano? How large is the shared range of a low clarinet, soprano saxophone and violin, and how might they best blend (unison, dissonant/consonant harmonies)?

There are countless ways in which instruments can be combined and my hope in including these suggestions is that you might think about interesting pairings/groupings. The listings below (within the description of each clarinet) are not exhaustive, do not guarantee good music and other combinations may be more successful within the musical context. Perhaps one of the most important things to bear in mind, especially when using unconventional pairings/groupings is balance: is any one instrument going to be naturally dominant over the others and spoil your imaginative combination? Can this be rectified by the use of different dynamic markings? Are extreme dynamics going to be reliable on certain instruments? All of these questions can be answered by experimentation and experience. Your notation software is not necessarily going to balance instrumental sounds in a realistic way.

High-range clarinets (piccolo clarinets in A-flat, G, E-flat and D, clarinets in C, B-flat and A, basset clarinets in C, B-flat and A)

For the purposes of this document I am dividing the clarinet family into three groups: high, mid, low. The high-range clarinets can also be divided into three sub-groups: piccolo clarinets, clarinets, basset clarinets. To my mind, these subgroups differ considerably in timbre, whilst still both being in the "highest" area of the clarinet family’s range.

Piccolo clarinets

These highest and smallest (hence: piccolo) of all clarinets come in at least 4 different nominal pitches: D, E-flat, G and A-flat, at least these are the most common types and even then — except for the E-flat clarinet — they’re quite rare. They are the upward extension of the sound of the clarinet family and can pierce the sound of a tutti orchestra with ease, when played in the high register. There are very few limits to the technical virtuosity possible on these instruments and when played softly, they can sound magical and seductive. Multiphonics on piccolo clarinets can be more difficult to produce than on the other high clarinets (C, B-flat, A) so be sure to always check them with someone. All other extended techniques work well.

The nomenclature “piccolo” may seem deceptive at first, because we are most often used to hearing or reading this word in association with the piccolo flute, which is pitched one whole octave above the standard flute. However, the term “piccolo” need not refer to an instrument one octave higher. The word “piccolo” comes from Italian and means small. As with much musical terminology in use in the English language, we have borrowed it from Italian. Because the word simply means small, which in woodwind-speak is the same as higher, this word can be applied to those members of the instrument family that are perceived to be significantly higher, proven by over 100 years of orchestration from three of the most significant national contributors to the classical music canon: Italy, France and Germany:

Italian: clarinetto in Do/Si-bemolle/La > clarinetto piccolo (=small) in Ré/Mi-bemolle/Sol/La-bemolle

French: clarinette en Ut/Si-bemol/La > petite (=small) clarinette en Ré/Mi-bemol/Sol/La-bemol

German: Klarinette in C/B/A > kleine (=small) Klarinette in D/Es/G/As

Next time you’re at the library, why not compare ways composers refer to the piccolo clarinet in E-flat, the most common piccolo clarinet?

Main article: piccolo clarinet in A-flat

Main article: piccolo clarinet in E-flat

Clarinets in C, B-flat and A

These three clarinets appear most often in orchestral writing and formed the core of the clarinet section before the higher and lower types of clarinets began to appear. During the time in which clarinets had only very few keys, a clarinet with a different nominal pitch, or transposition, could turn a "difficult" key into an "easy" key. For example, an overture in D major would call for clarinets in B-flat to play in E major, which having four sharps for a clarinet with as little as 5 keys (the mechanical kind) would have been quite a challenge, depending on the music. Playing the overture in D major on a clarinet in A would mean the clarinettist could play in F major, which having only one flat is much easier. Today, in part due to the fully chromatic keywork of modern clarinets, the necessity to change between B-flat and A clarinets on account of key signature has been minimised, even though music that uses key signatures of six or seven sharps or flats is difficult on any instrument, depending on the kind of writing, and changing instruments because of this may be worthwhile. The individual sonic qualities of the B-flat and A clarinets and the slightly larger range of the A clarinet are not to be underestimated in their ability to impact your music.

Clarinets in C appeared perhaps least often however they were quite noticeable because of their considerably brighter timbre. Clarinettists could use the same mouthpiece on a C clarinet so this was minimal inconvenience. C clarinets were used regularly in orchestral music from the mid 18th through to the early 20th century but their popularity has diminished since modern Bb and A clarinets now cover the full range of technical requirements needed, and so many — but not all — players have been transposing C clarinet parts at sight on B-flat clarinet for a century or so. The use of C clarinets today is something vaguely akin to historical performance practice: they are being used to get closer to the sound that composers wanted and there are some very good examples for this, particularly in the works of Ludwig van Beethoven, Richard Strauss and Gustav Mahler.

Main article: clarinet in C

Main article: clarinets in B-flat & A

Bass clef

Bass clef has been used since the 18th century when writing for clarinets capable of producing notes in the basset range of the instrument (written Eb3 to C3 or e♭ to c). As basset clarinets, today’s clarinet d’amore, basset horns and some very few types of alto clarinet fall into this category, a brief excursus into the use of bass clef when writing for clarinet is necessary at this point.

Almost all music for clarinet is written in treble clef due to the practice of playing the clarinet as a transposing instrument, i.e. a written middle C4 (c’) always sounds different depending on the clarinet played (see Transposition above). Earlier examples of music for clarinet show us that sometimes bass clef was used to delineate the context of musical material in the lowest register of the instrument (chalumeau) in contrast to higher passages in eg. the clarion register, that were written in treble clef. Ensemble or orchestral works in which the clarinet part essentially played the role of a bass or tenor voice for the duration, may have been written entirely in bass clef. Over time various conventions evolved that any low clarinet player must be able to navigate. The most common of these are French, German and Italian:

French notation: if bass clef is used at all, it is written one octave lower than the standard transposition, utilising the whole stave. Treble clef is read as normal. (see the above example)

German notation: bass clef and treble clef are written one octave lower, meaning that the clarinettist needs to play passages in treble clef one octave higher.

Italian notation: bass clef and treble clef both adhere to the instruments standard transposition, however much of the bass stave is rendered unusable.

If you as a composer or arranger want to use bass clef for a low clarinet part either in-part or entirely, I would recommend that you use bass clef as shown in the example above, in which the passages in bass clef are notated one octave lower. This enables a smoother visual transition from bass to treble clefs.

Basset clarinets in C, B-flat and A

The basset extension of the clarinet involves building an instrument with four extra chromatic pitches. It’s referred to as an “extension” because the notion of a basset clarinet “extends” the idea of the range of the instrument downwards. An extension does not mean that these low notes can be applied at will. The instrument (or at least the lower joint of the instrument) has to be build like this from the outset. The term “basset” comes from Italian: bassetto being the diminutive of basso and therefore meaning “small bass”. Indeed any kind of basset clarinet could be the bass voice of a small ensemble. The common types of basset clarinets are built with nominal pitches of C, B-flat and A, the last of which being the most popular thanks to the version of the Mozart Clarinet Concerto performed on basset clarinet in A. You may have to ask around a fair bit to locate an instrument in C or B-flat, but they do exist. Basset clarinets can play just as high as their standard range counterparts, but possess the four extra “basset” notes (written) Eb3, D3, C#3 and C3.

Mid-range clarinets (clarinet d’amore, basset horns in G and F, and alto clarinet)

The group of mid-range clarinets is less well-known when compared to the high- and low-range instruments but I am particularly fond of them. The definitions of and boundaries between mid-range clarinets were for a time unclear (i.e. clarinets d’amore, basset horns and alto clarinets were being made in all sorts of transpositions below middle C) but today, these have crystallised into a trinity of useful transpositions each a whole tone lower than the other (G - F - E-flat), and each instrument possessing unique sonic qualities: clarinet d’amore in G, basset horns in G and F and alto clarinet in E-flat.

At the time that instrument makers began experimenting with lower/alto clarinets, a trend was set in motion by the oboe family to do with bell shapes. The oboe d’amore had come about around 1717 and was used widely in masses and cantatas particularly in combination with plaintive, mournful music. The covered (=less rich in overtones) sound of the instrument has inspired composers to write for it, from Graupner and Bach through to Ravel and Debussy. Clarinet makers around 1740 began experimenting with bell shapes and found that the same kind of covered sound was attainable. Whilst the clarinet d’amore and its gentle sound didn’t enjoy the same success as the oboe d’amore, the instrument was employed in various guises until the mid-19th century.

The mid-range clarinets are the highest clarinets that exhibit slight bends over the course of the instrument on account of their size. The clarinet d’amore was the first instrument to exhibit a bend in the form of a curved metallic (mostly) or wooden (rarely) neck. The earliest basset horns however were first built in a completely curved form (much like the oboe da caccia) ending in a box — in which the bore makes several final curves — and a metal bell. The box enabled a range to low written C3 (c) (also known as the basset range, lit. small bass) and the metallic bell/horn was directly inspired by both the oboe da caccia and brass instruments, earning the instrument the name basset horn, which despite the modernisation of the instrument to look like an alto clarinet, has stuck. The modern alto clarinet in E-flat is considered to have developed after the d’amore and basset horn, even though low, straight clarinets (from nominal pitch G downwards) with flared, wooden bells in the 18th century were generally named alto clarinets. The alto clarinet was built in G, F and E, however developments in the regions now known as France and southern Belgium helped the instrument to migrate to its final nominal pitch of E-flat. Both the basset horn and alto clarinet have curved metallic necks and small, saxophone-like bells in the case of instruments manufactured in France, or upward pointing flared wooden bells if manufactured in Germany. Even though today the term alto clarinet applies only to the instrument with a nominal pitch of E-flat, there are major works in which an alto clarinet in F with a range to low written C3 / c is called for, which equates to the range of the basset horn in F.

A clarinet d’amore in G (Schwenk & Seggelke) and an alto clarinet in E-flat (Dietz Klarinetten) both with basset range to low C were invented in the 21st century. With technological advances making even better mid-range clarinets a reality and a resurgence of interest in rare instruments from both composers and clarinettists becoming evident, the future may be very bright for the often neglected and misunderstood mid-range clarinets.

Main article: clarinet d’amore / basset horn in G

Main article: basset horn in F

Main article: alto clarinet in E-flat

Low-range clarinets (bass, contralto and contrabass clarinet)

The group of low-range instruments is most commonly represented by the bass and contrabass clarinets, as well as their less well-known sibling the contralto clarinet. There were however more instruments created that today spend their lives in museums. Bass clarinets in C and A were manufactured for some time and a total of three octocontralto clarinets and one octocontrabass clarinet were made. Rising costs of materials and labour may explain the fate of these now obsolete instruments, but also streamlining in the way composers wrote for low instruments. Parts for bass clarinet in C and A became virtually non-existent after World War I. The emergence of the bass clarinet in B-flat as a solo instrument as early as 1928 (Othmar Schoeck — Sonata op. 41) piqued widespread interest and thus this instrument underwent a period of constant improvement during the 20th century. Today’s bass clarinets are masterpieces of technical ingenuity with improvements still being made.

Whilst the bass clarinet enjoyed a shining career in the symphony orchestra, the contralto and contrabass clarinets were relegated to the wind symphony, even though some works for orchestra with contrabass clarinet do exist. Nonetheless both of these instruments possess great potential as solo instruments, as already proven in some cases, and are a great asset to any kind of small to large ensemble. Makes of these instruments differ wildly to the extent that some solo pieces are written for a particular model and performances on other models have to be "adapted". The way multiphonics behave from instrument to instrument is also quite different.

Essentially all three instruments (bass, contralto, contrabass) offer strong bass voices, a wide variety of spectral, fingered and dyadic multiphonics and all other extended techniques. The character of the sound of each instrument should be investigated up close to determine which instrument is right for you. Please refer to the section on writing in bass clef for clarinet as this is most applicable to these instruments.

Main article: bass clarinet in B-flat

Main article: contralto clarinet in E-flat

Main article: contrabass clarinet in B-flat